Humanities: Amherst County Historic Schools Project

Digital Media Oral History Presentations and Documentaries:

“Three Amherst Schools: The Bear Mountain Mission School,

Amherst County Training School, and Clifford School”

|

|

|

In 2009-2010, AGAR interviewed teachers, staff, parents and students who worked and studied at these three segregated schools prior to mandatory integration. Lynn Kable was project director for this program and Mia Magruder was camerawoman and editor. Lynn Rainville, PhD and Kurt Ayau, PhD were project humanities advisors.

You may watch these videos on Discovery Virginia, the Virginia Humanities Digital Archive:

You may watch these videos on Discovery Virginia, the Virginia Humanities Digital Archive:

|

Click link below to watch.

https://discoveryvirginia.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A12325 |

Click link below to watch.

https://discoveryvirginia.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A12324 |

Click link below to watch.

https://discoveryvirginia.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A12323 |

Please contact AGAR with inquiries about the project:

Email Lynn Kable, project director, [email protected] or call 434-989-3215.

Email Lynn Kable, project director, [email protected] or call 434-989-3215.

“African-American Schools in Amherst County

and Early Integration”

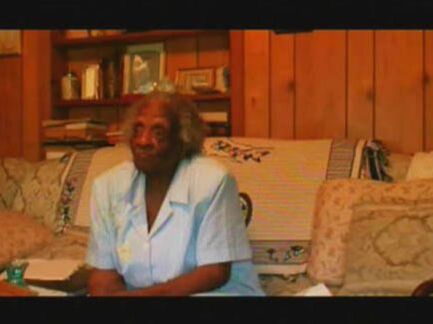

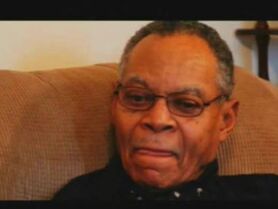

In 2011-2012, AGAR interviewed African-American former teachers, parents, and students. These individuals gave first-person accounts of their experiences at early-and mid-twentieth century Amherst County segregated small and consolidated schools, and of school integration in the 1960s and early 1970s. AGAR interviewed over 35 individuals ranging in age from their 50s to 103 about experiences of attending one-room schools, of opening the new "modern" segregated Central High School in the 1950s, and of being the first African-Americans to attend previously all-white schools in Amherst County.

You may watch these videos on Discovery Virginia, the Virginia Humanities Digital Archive:

You may watch these videos on Discovery Virginia, the Virginia Humanities Digital Archive:

|

Click link below to watch.

https://discoveryvirginia.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A12105 |

Click link below to watch.

https://discoveryvirginia.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A12106 |

African-American Schools in Amherst County, Virginia:

Students, Parents, and Teachers Interviewed by AGAR for its 2011-2012 Project

(Before public schools were formed in Amherst County, there were 84 independent schools: 69 white schools,

14 black schools and 1 Indian mission school)

Students, Parents, and Teachers Interviewed by AGAR for its 2011-2012 Project

(Before public schools were formed in Amherst County, there were 84 independent schools: 69 white schools,

14 black schools and 1 Indian mission school)

|

Education in Amherst County has changed remarkably in the past 60 years, and elders from the rural parts of our community chuckle as they tell of trying to explain to their grandchildren that they had to carry buckets of water every day from a stream to their one-room or two-room schools, that they left for home when it started to get dark because there were no lights, and that they used outhouses. The grandchildren simply don’t believe it, telling their grandparents to “Stop trying to pull my leg.” For African-American elders of an earlier generation, those who graduated from elementary school prior to 1923-24 (According to the Rosenwald School website) in Northern Amherst County and prior to 1939 in Southern Amherst County, there was no free public high school education after seventh grade. For the sons of sharecroppers and farmers, it was sometimes necessary to leave school even before finishing elementary school for economic reasons. Girls also left school early to make money for their family, often through domestic or agricultural work. Parents who themselves had little or no formal education urged their children to attend school to increase their opportunities and better the future of the next generation.

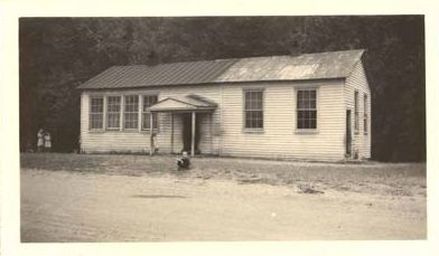

Parents who struggled for employment during the depression and lived through World War II urged their children in the 1950s to finish high school and go on to College. Some, whose educational opportunities had been limited to elementary school, even went back to high school night classes in order to gain their GED degrees and attend college classes. They told AGAR with pride of their daughter the teacher, their son the minister and their granddaughter who recently received a PhD. We heard many remarkable and touching stories from people who have lived meaningful lives in periods of difficulty and change. We are pleased to be able to share their oral histories with others. Students who were among the first to integrate previously all-white elementary, junior and high schools in the 1960s also shared touching incidents and tributes to their parents and grandparents who urged them to be pioneers, and to get the best education possible, however difficult it was at times. Parents and teachers of these students also shared their memories of experiences during the 1960s and early 1970s. Information about the dates the schools were built, and materials used for each school was taken from the 1941 Amherst County Public School Engineers Report unless otherwise noted. Two of the schools whose students we interviewed, Blair and Ware (aka Turner-Ware), were no longer listed as existing in 1941. This report was posted to the Amherst County Schools website for the 100th anniversary of the Town of Amherst in 2010 under “administration.” Former School Superintendent Tyler Fulcher’s book “A FRONT LINE VIEW ON THE FRONT LINE OF LIFE” contains photos and information about the Amherst schools when he took office in 1953. Some of the text was written, according to Fulcher while he was superintendent, the rest after he retired. The book itself was published with a copyright of 1972 and does not have a publisher listed. Hard copies can be found in the Amherst County Museum, and those interested in studying this period are encouraged to drop by and read the entire book. In Fulcher’s book he explains that when he became Superintendent in 1953, the County Sanitarian had finished inspecting all the county schools and had found over half of them to be unsafe or unsanitary, especially, needless to say, the small schools that dotted the countryside. Fulcher’s first job was what he called “Patch-Up.” Several of the schools had students fetch their only drinking water from springs in cow pastures. The Health Department now required building fences around the springs. Many of the schools needed new outdoor privies (outhouses). Superintendent Fulcher said, “During the patch-up period the cows, the calves, the horses and the mules and I became well acquainted. In addition to these acquaintances, I felt a degree of proficiency in the building of out-of-door sanitary conveniences. In my patch-up expeditions I visualized better things to come. I saw, in imagination ‘Great Edifices of Learning’ unequaled in the ‘land’.” (Fulcher, Tyler, A.B., M.A., L.L.B., Dag.S. A Front Line View on the Front Line of Life, 1972. Page 41.) By the time Superintendent Fulcher retired he and the teachers, parents and students of Amherst County had seen the building of two high schools, new elementary and junior high schools as well as the start of school racial integration. AGAR has been given permission to use the contents of the 1941 Amherst County Public Schools (ACPS) Engineer’s Report by Superintendent of schools Dr. Brian Ratliff. AGAR was given the “ON MAP” locations of the schools by longtime Amherst County residents Darnell Woodruff Winston and Jasper Fletcher. AGAR was given permission to use County’s map by Gary Roakes of the Amherst County Department of Public Safety. The map “square” on which each school is located is listed on each school’s write-up below shows its location on the official Amherst County Map. Holly Mills of the Amherst County Museum helped AGAR to locate integration and school-closing dates from the Amherst County and Lynchburg newspapers of the time. The Small African-American Schools (one- two- or three- rooms) Scott Zion School Square160 (Now would be on Galt’s Mill Road next to the old Scott Zion Church, sometimes spelled Scottzion School as in Superintendent Fulcher’s book.) Built originally in 1906, the school has since been demolished to make a parking lot. In 1941 the location was “On Goff Hill-Wright Shop Road 5 miles East of Madison Heights.” According to 1941 ACPS Engineer’s report this was a one-story frame building with a metal roof and a brick foundation. It had wood board floors and wood ceiling, electric lights and stove heat. Our project interviewed former students Roosevelt Christian, Bernard Jackson, Mary Jackson, Samuel and Dorothy Jackson, Irving Reed and James Reynolds. St. Domingo School was described in 1941 ACPS Engineer’s report as “2 miles East of Madison Heights.” It was built in approximately 1908 as a one-story frame building with concrete foundations and metal roof. It had wood board floors, wood ceilings, no lights, and stove heat. According to Dr. Fulcher in his book, this school was one of those most in need of repair when he took office in 1953 (Fulcher, Tyler, AB, MA, LLB, Dag.S. A Front Line View on the Front Line of Life, 1972. Pages 42-45). The school has now been demolished. Interviewed for this project was former student Russell Lee. Mt. Airy School was described in the1941 ACPS Engineer’s report as “one mile from Faulconerville Store on Old Stage Road.” Built approximately in 1920, it was a one-story frame building, relatively large, with metal rood and concrete foundation, frame walls, wood floor and wood ceiling. This school is listed on the Rosenwald School website. The school had electric lights and was heated with stoves. It also had coal stoves in a kitchen for cooking. The last of the small African-American Schools to be closed (it was the only one voted to be kept open in 1964-65). Mt. Airy became obsolete with integration and has now been demolished. Project interviewed former students John Jasper Smith, Barbara Hutcherson Parks and Rosa Johnson Brown. Ware School (aka Turner-Ware School) was located on the corner of what is now Dixie Airport and Amelon Roads in Madison Heights. A very early Southern Amherst African-American school — date built unknown to us — has since been demolished. The school was no longer operating in 1941 when the ACPS Engineering report was written. Project interviewed former student Mary Jackson and was also discussed in the interview with Roosevelt Christian. (No photo available.) Puppy Creek School, east of Pleasant View, was built approximately in 1920. According to the 1941 ACPS Engineer’s report, this was a one-story frame building with a metal roof and stone foundations. It stood, the report said, on the “West side of Route 610, three miles south of Route 60.” Project interviewed former student Martha Turner. Timothy School was built approximately in 1917 in Pleasant View (south of Allwood on current Amherst County map). According to the 1941 ACPS Engineer’s Report, this was a one-story frame building with stone foundations and a metal roof; it had wood board floors and ceiling, no lights, and was heated by stoves. AGAR’s project interviewed former student Mabel Massie Hughes. Madison Heights Two-Room Negro School was an early Madison Heights School and has since been demolished. Built date of this two-room school is unknown and was replaced by Madison Heights Colony Road School (same location, brick, opened in 1939). Project interviewed former student Hazel Thompson. Moss Hill School (AKA Moss Rock School) According to the 1941 ACPS Engineer’s report description it was located on Route 60, one-half mile Northwest of Forks of Buffalo. It was a one-story frame building with concrete post foundations and a metal roof, having wood board floors and a wood ceiling, no lights and stove heat. The school was built in approximately 1934. It fell down in 2012 according to neighbors. Project interviewed former student Lula Hendrix Perry. St. Mary’s School in the 1941 ACPS Engineer’s report was said to be on “Route 620 near junction of 621.” (These are different route numbers now, near Lowesville.) The school was built in approximately 1918. According to the ACPS 1941 Engineer’s Report, this was a one-story frame building with concrete foundations and metal roof, frame walls and wood floors, wood ceiling, lighted with lamps and heated with stoves. The project interviewed former student Irene (Bessie Mae) Coyle. Ivey Hill School (aka Ivy Hill School) This school was one-half mile west of Naola. This version (photo from 1941 ACPS Engineers’ report) is a one-story frame building with a metal roof and concrete foundations, wood board floors and wood ceiling, no lights and stove heat. School pictured was probably built in 1929. Project interviewed former student Robert Perry who said his mother told him the school burned several times. |

sChestnut Grove School According to 1941 ACPS Engineer’s report information, the school stood on Salt Creek Road 2 miles west of Elon, a one story frame building with stone foundations and a metal roof, no lights, and stove heat. It was built in approximately 1906 and now demolished. Project interviewed former students Mary Woodruff and her daughters Darnette Woodruff Hill and Darnell Woodruff Winston, and Robert Perry.

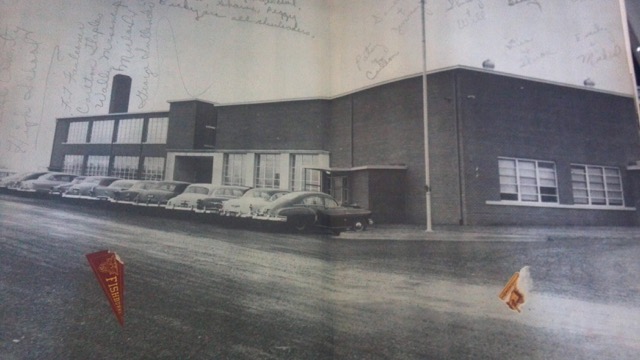

Clifford School (Colored) was located on Route151 just west of Winton Road (on the property of St. Peter’s Church). Now demolished, the school was built in approximately 1916. The ACPS 1941 Engineer’s report described the schools as a one-story frame building with concrete foundations and a metal roof, with wood board floors and ceiling, no lights, and stove heat. Interviewed for the project was former student Norman Fletcher. Blair School was said by Annabelle Turner, “to have been located near the corner of current Route 29 and Toytown Road next to Rucker’s store.” No longer a school in 1941, this was the school where Annabelle Turner, now 103, attended elementary grades, not having the option to go to a public high school. Now demolished, dates when built and torn down are not known to us. Interviewed for project was Annabelle Turner. Oak Hill School According to the 1941 ACPS Engineer’s report, was located one mile west of Mt. Moriah Church on Fancy Hill and Mt. Moriah Roads. It was a one-story frame building with concrete foundations and metal roof, wood board floors, wood ceiling, no lights, and stove heat. It was built in approximately 1934. Interviewed for project was former student Eva Jones. The Larger Schools Amherst County Training School was located at what is now the dead end of School Street in the town of Amherst. The brick building that housed two classrooms now is the WAMV Radio Station. The small white wood cafeteria building is also still standing. The main school, a frame building, was demolished after the school closed in 1964. The main building was built according to the Rosenwald Schools website in 1923-24, but more rooms and two buildings were added over the years. This school was built partially with funds raised by parents and children as well as black-owned businesses. Closed as a high school when Central High School was built in 1956, the elementary school continued there until it closed in 1964 when Central Elementary School opened. Interviewed for this project were former students Rosa Johnson Brown, Annie Higginbotham Carpenter, Norman Fletcher, Eva Jones, Barbara Hutcherson Parks, John Jasper Smith, and Martha Turner. (Please see AGAR’s 2010 film, “Three Amherst Schools: Amherst Training School,” for which additional students and teachers were interviewed at Discovery Virginia, the Virginia Humanities digital archive site, https://discoveryvirginia.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A12324). Madison Heights / Colony Road School (Officially called in its early days the Madison Heights School for Negroes.) This School taught students in grades one through eleven and replaced an earlier two-room wooden elementary school at the same site. This building was built partially with funds raised by parents and children and contributions from black-owned businesses. Located on Colony Road in Madison Heights, this building stands today and is occupied by a church-run program. The new brick school was both an elementary school and the first public high school for the students of the southern end of Amherst County. It opened in 1939. The high school closed when Central High School opened in 1956. The school continued to operate as an elementary school, later called the James River Elementary School, until the current Madison Heights Elementary School was built and opened for the 1991-1992 school year. Interviewed for this project were former teacher Clara Jackson and former students Roosevelt Christian, Melodie Campbell Fletcher, Samuel Jackson, Dorothy Jackson, Beverly Campbell Jones, Darnette Hill, Russell Lee, Leon Parrish, Louise Ware Reed, Irving Reed, Robert Perry, James Reynolds, Juanita Campbell Roberson, Larry Thomas, Charles Thompson, Hazel Thompson, and Darnell Winston. Central High School is a brick structure on Route 60, west of the Town of Amherst. It opened as a segregated high school in 1956, and for the first time in Amherst County, contained a twelfth grade year for African-American students. Students who had finished the 10th grade in the final year of operation of Amherst County Training School and Madison Heights Colony Road were permitted to complete both 11th and 12th grade courses at Central High School in its first year and receive a high school diploma from twelfth grade. After that school year, the school taught grades eight through twelve. Beginning in 1962, students who chose to transfer to Amherst County High School were allowed to do so and to attend integrated classes. Teachers were also integrated, with several African-American teachers transferring to Amherst County High School and White teachers teaching at Central High. Central High School closed in December 1969, with all remaining students transferred to Amherst County High School. The school reopened in late January 1970, as an integrated junior high school and operates today as Amherst Middle School. Former teachers interviewed were Herman Frederick and Clara Jackson. Former students interviewed included Rosa Johnson Brown, Irene (Bessie Mae) Coyle, Beverly Jones, Eva Jones, Russell Lee, Leon Parrish, Barbara Hutcherson Parks, Robert and Lula Hendrix Perry, Louise Ware Reed, James Reynolds, Juanita Roberson, Larry Thomas, and Charles Thompson. Central Elementary School, a brick structure opened in 1964 on Route 60, west of Amherst (next to Central High School), as an African-American segregated school. Beginning in 1962, African-American students who wished to do so could ask to attend previous-all-white elementary schools closer to their homes, and several families immediately did. Students who attended Central Elementary were from the Town of Amherst and the Northern end of the county. When court-ordered mandatory integration took place, Central Elementary closed as a segregated school in December 1969 only to open again as integrated in January 1970. Some African-American students were transferred to schools nearer their homes, while some continued to attend Central Elementary with white students attending as well. Some African-American teachers continued to teach at Central while others were transferred to teach at previously all-white schools, with white teachers switching into Central. Central Elementary School continues to operate as a public elementary school in Amherst today. Interviewed for this project were former teachers Beverly Campbell Jones and Gloria Higginbotham, and former student Teresa Henley. These are only the Amherst County African-American schools from which the Amherst Glebe Arts Response, Inc. (AGAR) interviewers were able to interview students or teachers at this time. There were several other small African-American schools. ___________________________________ In addition to the segregated schools, AGAR interviewed teachers, parents and students from the African-American community who were pioneers in integrating elementary and high schools in Amherst County and elsewhere. These included teachers Herman Frederick, Gloria Higginbotham, Clara Jackson, and Beverly Jones; parents Mabel Hughes, Hazel Thompson, and Mary Woodruff; and students Melodie Campbell Fletcher, Teresa Henley, Darnette Woodruff Hill, Charles Hughes, James Reynolds, Angela Woodruff Scott, Charles Thompson, Darnell Woodruff Winston and Ronald Wright. These were brave individuals and families who did what they believed was right for the future good of Amherst County and all Americans. In Amherst County, there was also the Bear Mountain Mission School that taught Monacan Indian children from the late 19th century until 1963-64 when the Monacans transferred to previously all-white schools in Amherst County. (Please see AGAR’s 2010 film, “Three Amherst Schools: Bear Mountain Mission School,” at Discovery Virginia, the Virginia Humanities digital archive site, https://discoveryvirginia.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A12325 There were 86 schools in Amherst county over the years which included quite a number of all-white schools. AGAR has only had the opportunity to debut a film about the Clifford School, a rural school that served New Glasgow and Clifford white children. AGAR’s oral histories on digital media were supported in part by a discretionary grant from the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and by a grant from the Greater Lynchburg Community Foundation. |

AGAR First-person Interviews: Amherst County Schools

Early 20th Century through 1975

Amherst Glebe Arts Response, Inc. (AGAR) conducted a total of 57 first-person interviews about attending, being a parent, or teaching at Amherst County Public Schools from the early 20th Century through 1975.

Project Humanities Advisor was Dr. Lynn Rainville.

Project Humanities Advisor was Dr. Lynn Rainville.

" Schools in Amherst County and Early Integration" The project was partially funded by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities (VFH) 2013-2015. Some of those interviewed were associated with four or five schools as students, parents, and/or teachers. All 57 interviews were transferred to individual DVDs and 38 have been transcribed as well. Interview DVD copies have been archived with Virginia Foundation for the Humanities (VFH) and Amherst County Museum and Historical Society (ACM).

The project also resulted in 21 short documentary videos about Amherst County Schools in addition to the 57 first-person interviews, all of which were archived at the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities Office, the Amherst County Museum and Historical Society and by AGAR.

Copies of DVDs of the original individual interviews were given or mailed to the person interviewed or their families if they had passed on.

The current project built upon two previous AGAR interview and documentary projects, "African-American Schools in Amherst County and Early Integration" and “Three Amherst Schools: The Clifford School, Amherst County Training School, and Bear Mountain Indian Mission School,” also archived at VFH and ACM.

The project also resulted in 21 short documentary videos about Amherst County Schools in addition to the 57 first-person interviews, all of which were archived at the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities Office, the Amherst County Museum and Historical Society and by AGAR.

Copies of DVDs of the original individual interviews were given or mailed to the person interviewed or their families if they had passed on.

The current project built upon two previous AGAR interview and documentary projects, "African-American Schools in Amherst County and Early Integration" and “Three Amherst Schools: The Clifford School, Amherst County Training School, and Bear Mountain Indian Mission School,” also archived at VFH and ACM.

AGAR Project of First-Person Interviews and Documentaries Now Archived and Available

The following twenty-one documentary films have been created on seven DVDs to tell the stories of the schools studied in the words of those who taught at or attended or were parents at them. Copies have been given to the Amherst County Museum and will be delivered to the VFH:

|

Disc One

Disc Two

Disc Three

Disc Four

|

Disc Five

Disc Six

Disc Seven

|

Interviewers and Memorabilia for 2013-2014 Project

|

AGAR Interviewers: Interviewers included Sandra Esposito, Edward Kable, Lynn Kable, Kathryn Pixley, Kitty Swanson with outreach assistance from Beverly Keith Campbell, Beverly Campbell Jones, Jean Higginbotham and John Gatewood. Interviewers received training from Donovan Media Center and/or Lynn Rainville, PhD.

Videographer: Ned Kable was videographer for all project interviews, and copied the individual interviews onto DVDs. Individual interviews appear on one DVD (or, in a few cases, two friends, father and son, or a married couple in same interview.) Equipment for this project was purchased through a grant from Greater Lynchburg Community Trust and Ned Kable was trained in its use by Bill Noel of Donvan Media Development Center. Videographer for previous projects in 2009-2012 was Mia Magruder. Photos and Memorabilia: AGAR received access to memorabilia (especially yearbooks) and photos from Jacqueline Beidler, Mary Brugh, Judith Faris, Louise Faulconer, Leah Settle Gibbs, Ella Magruder, Helen |

Massie, Florence, Holcomb, and Alan Nixon, Kathryn Pixley, Marita Taylor, Bob and Betty Wimer, and from Amherst County Museum and Historical Society, the Amherst County Public Schools and the Amherst County Public Library.

School Sites: AGAR was able, with the help of local historians Florence and Holcomb Nixon and Beverly Keith Campbell, to view and photograph sites, and remains of several schools no longer existing. These include: Macedonia Church (outhouses still standing); Edgewood at Pera School (still standing); Pearch School (no longer); Oak Grove/Pedlar District (church and school fell down, church foundation visible): Pedlar Mills School (went down Pedlar River in hurricane Camille); African-American school Timothy (near standing Timothy Church, school torn down); and African-American school Chestnut Grove Baptist Church (school torn down, church is there). |

Please contact AGAR with inquiries about the project:

Email Lynn Kable, project director, [email protected] or call 434-989-3215.

Email Lynn Kable, project director, [email protected] or call 434-989-3215.